Trauma-Informed Practices: Building Safe, Supportive Spaces for Neurodivergent and Disabled Learners

Trauma can touch anyone, no matter their age or background, and it can seriously impact a person’s ability to learn, trust others, and communicate openly. For neurodivergent and disabled learners especially, trauma-informed practices play a vital role in creating environments where they can feel safe and supported.

Before the term “trauma-informed” permeated our vocabulary, trauma existed.

Trauma has always existed.

And it will always exist.

For educators, therapists, and other professionals working with neurodivergent and disabled youth, understanding how trauma affects people—and using trauma-informed practices—can make a huge difference. These approaches help create safe, supportive environments that encourage healing and growth instead of unintentionally adding more stress or harm.

In this post, we’ll dive into what trauma-informed practices are, why they’re especially significant for neurodivergent and disabled learners in educational and therapeutic spaces, and share practical strategies for putting them into action.

Using these methods, professionals can create environments where all students, clients, and patients—including those with neurodivergent and disabled identities—feel safe, respected, and understood.

Disclaimer: Trauma-informed practices are not the same as trauma therapy. While trauma-informed approaches focus on creating safe, supportive environments and understanding the effects of trauma, they do not involve directly treating trauma. Children and families should always seek proper mental health support from qualified professionals if trauma treatment is needed.

Adult comforting a child experiencing distress using trauma-informed strategies

Definitions of trauma: Perspectives for neurodivergent and disabled communities

Understanding trauma through various lenses helps provide a more inclusive perspective, especially for neurodivergent and disabled individuals who may experience unique forms of trauma.

Below are some valuable definitions from respected resources and community-driven perspectives:

Merriam-Webster: Defines trauma as “a disordered psychic or behavioral state resulting from severe mental or emotional stress or physical injury.”

American Psychological Association (APA): “An emotional response to a terrible event like an accident, crime, natural disaster, physical or emotional abuse, neglect, experiencing or witnessing violence, death of a loved one, war, and more.”

The Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN): “Incidences of trauma, in autistic and developmentally disabled people no less than in the general population, are adverse health events in and of themselves and have long-term effects with other negative consequences for survivors’ physical and mental health. The central goal of any best practice guidelines this process produces must be the prevention of these harms through the reduction or elimination of medical trauma. “

Fireweed Collective: Describes trauma as “complex, and not all trauma is traumatizing. The level of traumatization is not relative to the magnitude of the trauma, but to the social and emotional support in the aftermath of the traumatic event. Support includes a strong cultural identity, nurturing close relationships, and safe access to housing, food, and healthcare. When we show up for each other, we protect each other and our communities from the effects of traumatization.”

What are trauma-informed practices?

Trauma-informed practices recognize that trauma shapes the way people interact with others, respond to authority, and handle daily stress.

Instead of asking, “What’s wrong with you?” these practices reframe the question to “What happened to you?” This shift helps us understand people’s experiences rather than judging their reactions.

Without a trauma-informed approach, people who’ve been through trauma may feel misunderstood or even retraumatized, even in supportive environments.

Instead of asking, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ trauma-informed practices ask, ‘What happened to you?’

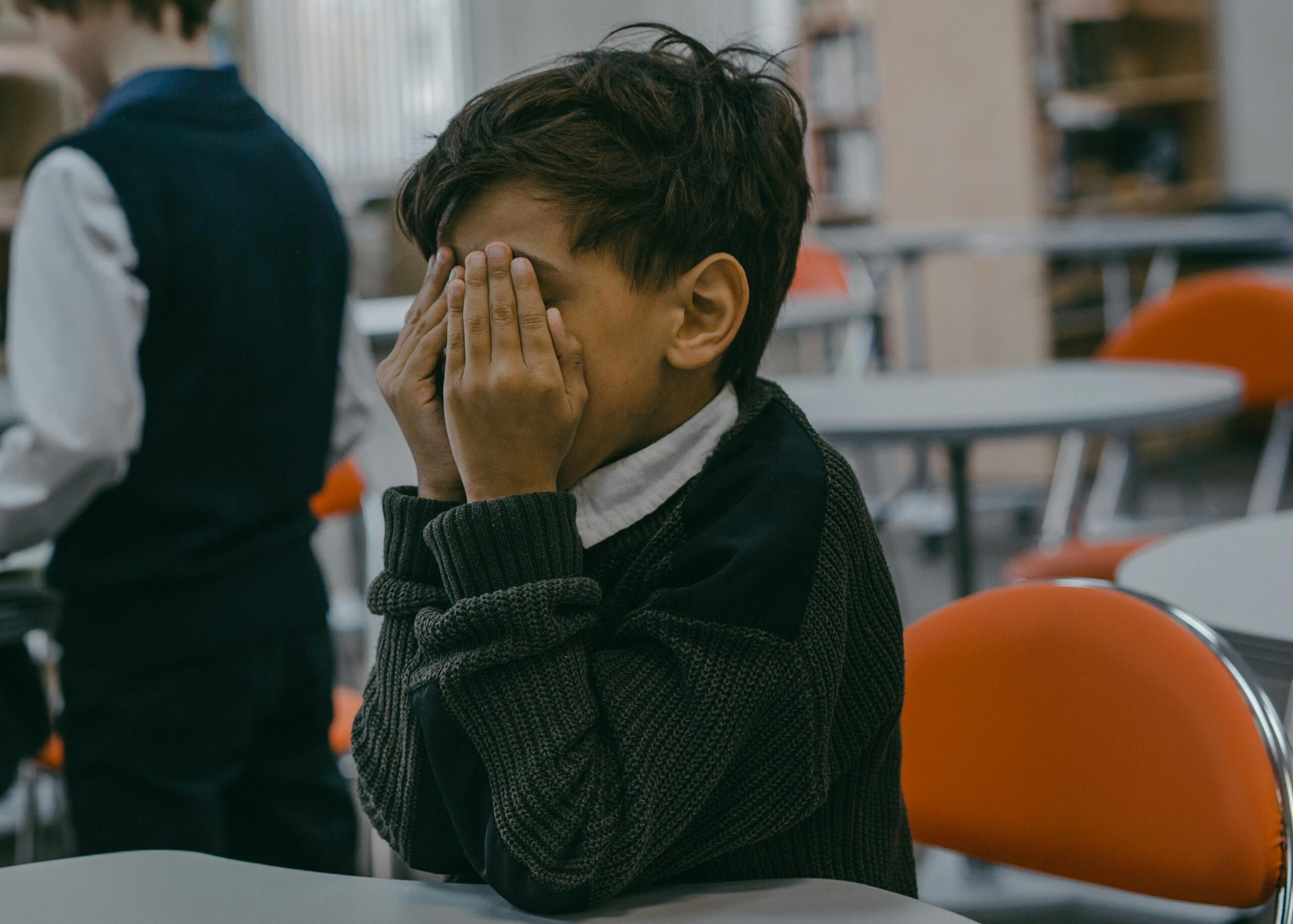

A distressed child can benefit from trauma-informed practices

Why trauma-informed practices matter more than ever

How Trauma Affects the Brain

When someone goes through a traumatic experience, it changes how their brain works.

Parts of the brain involved in spotting danger—like the amygdala—can get stuck on high alert, constantly scanning for threats, even in safe situations. Meanwhile, the brain’s “thinking center,” responsible for things like planning and decision-making, can struggle to keep up. This imbalance makes it hard for individuals affected by trauma to focus, feel safe, or trust others easily.

Trauma-aware practices understand this brain science and aim to create safe, predictable spaces that help calm the brain, reducing stress so people can feel more at ease and open to learning or healing.

A Shift in How We Approach Trauma

In the past, standard practices in schools and therapy often missed the impact of trauma. Traditional methods focused on managing behaviors or following set protocols without fully understanding what trauma does to people.

As research expanded, professionals realized that without addressing trauma, their efforts could unintentionally make things worse or slow down progress.

Today, trauma-aware practices are seen as an essential part of ethical, effective care. In education and therapy especially, understanding and addressing trauma has become crucial for creating safe, respectful spaces where real flourishing can happen.

Get more anecdotes and strategies like this one

Sign-up to my newsletter for professionals

By signing up for email alerts, you agree to receive updates and promotions to support you in your role in education or therapy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Understanding ACEs: Adverse Childhood Experiences and their impact on trauma

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, refer to potentially traumatic events that occur during childhood, such as abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction. The concept of ACEs comes from a groundbreaking study by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente, which found that these early experiences can have long-lasting effects on physical and mental health.

For neurodivergent and disabled children, these impacts can be even more complex, as they may already face additional stressors or misunderstandings in their environments.

It’s important to note that by the time neurodivergent and disabled learners land in your classroom or on your caseload, they have already experienced trauma. Being born in a body that dominant culture does not consider “normal” automatically has an impact on the child’s emotional well-being. This is true of marginalized communities at large.

By simply existing as neurodivergent and/or disabled, learners have already experienced trauma.

Why neurodivergent and disabled learners often face trauma

For neurodivergent and disabled learners, just moving through the world can bring repeated experiences of stress and misunderstanding simply because of who they are. Many schools and social spaces aren’t designed with the unique needs of people in mind, which can lead to experiences that feel isolating, frustrating, or even scary.

Over time, these repeated situations can lead to trauma, as neurodivergent and disabled individuals encounter environments where they feel excluded, judged, or misunderstood.

In classrooms, for example, neurodivergent students are often disciplined or required to conform to “behaviors” related to their neurological traits, like sensory preferences. Instead of receiving support, they may be labeled as “difficult” or “problematic.” Educators and therapists may focus on “fixing” rather than accepting.

Disabled students face similar struggles when they don’t get the accommodations they need. They may feel stigmatized for requiring extra assistance. All these negative experiences build up, making disabled folks feel unsafe or unwelcome in spaces meant to support their growth.

These repeated, stressful encounters can lead to trauma, causing neurodivergent and disabled learners to feel anxious, avoid situations, or mistrust authority figures.

Trauma-informed practices in a classroom setting help children in distress

Understanding intersectionality in trauma-informed practices

Trauma doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Each person’s experience with trauma is influenced by different parts of who they are—like their race, gender, disability, neurodivergence, and background.

Intersectionality, a concept coined by scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, helps us understand how these overlapping identities shape a person’s life, including the challenges and trauma they may face.

For neurodivergent and disabled learners, trauma isn’t only about disability or neurodivergence; it’s also affected by things like culture, socioeconomic background, and past experiences with authority figures.

Disabled students from lower-income backgrounds may have less access to resources or support, while LGBTQ+ disabled learners might face settings that don’t fully recognize or respect their identities. These overlapping factors can intensify the trauma they experience.

How trauma-informed practices differ from traditional approaches in supporting neurodivergent and disabled learners

| Traditional Approaches | Trauma-Informed Practices | |

| Primary focus | Focuses on controlling behavior without addressing root causes | Emphasizes understanding the underlying causes of behavior, especially from trauma or stress |

| Approach to discipline | Often relies on punitive measures, like detention or exclusion, which can increase stress | Uses empathy, understanding, and supportive redirection to support the learner |

| Design of the environment | Generally uses standardized layouts that may not account for sensory needs or individual differences | Creates safe, sensory-friendly spaces, often with quiet zones and flexible seating |

| Communication style | Authority-driven communication that may not fully explain decisions, fostering compliance rather than trust | Open, transparent communication that explains actions and seeks to build trust |

| Response to emotional distress | Often views distress as misbehavior or non-compliance, with limited accommodations for self-regulation | Validates emotions and offers calming tools, like grounding exercises or sensory items |

| Role of student/client choice | Typically prescribes set activities and schedules with limited choice, focusing on conformity | Encourages choice and autonomy, letting learners decide how they engage or when they need breaks |

| View of behavior | Views behavior as something to be corrected, and the child’s fault | Sees behavior as communication, understanding that stress or trauma may influence actions |

| Impact on mental health | Can exacerbate anxiety or stress by not addressing underlying emotional needs | Aims to build self-esteem and coping skills by supporting mental health needs |

| Long-term impact | Can lead to feelings of mistrust, anxiety, and avoidance in educational or therapeutic settings | Helps build confidence, self-advocacy, and emotional regulation skills that extend beyond the classroom or therapy room |

The lasting benefits of trauma-informed education for neurodivergent and disabled learners

Trauma-informed practices aren’t just about helping neurodivergent and disabled students feel supported right now. They can have lasting, positive effects on their future, too. When learners feel understood and respected, they’re more likely to develop important skills and confidence that stay with them for life.

Here are some of the ways trauma-informed education can help build a strong foundation for neurodivergent and disabled students:

- Build coping skills

- Boost self-esteem

- Improve academic experiences

- Improve social experiences

- Develop self-advocacy skills

- Develop self-awareness

- Support long-term mental health

Offering choices gives students a sense of control and shows that their voices matter—an essential part of trauma-informed care

Calm children in a classroom setting that uses trauma-informed practices

Strategies for trauma-informed practices with neurodivergent and disabled learners

1. Cultivate a safe, supportive neurodiversity- and disability-affirming environment

Create spaces where all students or clients feel both physically and emotionally safe. For neurodivergent and disabled learners, this can mean having predictable routines, reducing overwhelming sounds or visuals, and providing quiet zones for when things get too intense.

2. Build trust through transparency

Be open and clear about what you’re doing and why. If you’re requesting or suggesting an activity, explain the ‘why’ behind it. When learners feel informed and included, they’re more likely to engage without feeling anxious or uncertain.

3. Understand and accommodate triggers

Each person has unique triggers—things that might remind them of past stress or trauma. They can also be regarded as stress responses or stressors.

Triggers could be sounds, unexpected or varying forms of touch (or touch at all), certain words, or even eye contact. For neurodivergent learners, sensory overload can be a big trigger. Being aware and accommodating of these triggers helps avoid stressful situations.

4. Practice empathy and validation

Take time to listen and acknowledge what each person might be going through. For many neurodivergent and disabled learners, school or therapy settings may have been places of misunderstanding or frustration in the past. Validating their feelings by saying things like “I hear you” or “That sounds tough”—can make learners feel seen and respected.

5. Promote choice and autonomy

Offering choices gives students and clients a sense of control over their experiences. Let learners decide how they want to participate or if they need a break. Neurodivergent and disabled individuals often feel restricted by rules that don’t suit their needs, so giving them choices helps them be a part of the process.

6. Use simple tools for emotional regulation

Introduce calming techniques like deep breathing, grounding exercises, or mindfulness practices. For neurodivergent learners, having tools can be especially helpful in managing sensory overload or feelings of stress, giving them ways to find calm on their own terms.

7. Commit to ongoing learning and reflection

Trauma-informed care isn’t one-and-done; it’s an ongoing journey. Continuous learning and self-reflection help educators and therapists stay aware of the best ways to support neurodivergent and disabled individuals.

A child engaged in self-regulatory practices

Common pitfalls to avoid in trauma-informed practices with neurodivergent and disabled learners

1. Overlooking personal bias

We all have biases—opinions or assumptions we may not even realize we hold—that can shape how we interact with others. For neurodivergent and disabled learners, these biases might come across as unfair assumptions about their abilities, needs, or behaviors.

2. Overlooking cultural differences

Every student or client has their own story and needs. Trauma-informed care includes respecting each person’s cultural background and understanding how their culture influences their responses to stress, trauma, and healing. Take the time to understand how each person’s unique identities shape them.

3. Assuming trauma is always obvious

Trauma doesn’t always show up in ways that are easy to see. Neurodivergent and disabled learners may have unique ways of expressing themselves, and not all signs of stress or trauma are visible. It’s important not to make assumptions based on how someone looks or behaves. Instead, approach each person openly and let them show you who they are and what they need.

Resources

An overwhelming amount of resources are available, and sometimes, they can block you from beginning this journey. I caution you to be selective about the resources you find. Some types of support are harmful to or negligent of the experiences of neurodivergent and disabled individuals as they often don’t consider their wholeness (gender identity, sexual orientation, culture, neurotype, socio-economic status, etc.).

My recommendations take these points into account.

Books

- Bascom, J. (2014). The obsessive joy of autism. The Autistic Press.

- Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing.

- Delahooke, M. (2019). Beyond behaviors: Using brain science and compassion to understand and solve children’s behavioral challenges. PESI Publishing & Media.

- Greene, R. W. (2008). Lost at school: Why our kids with behavioral challenges are falling through the cracks and how we can help them. Scribner.

- Katz, J., & Lamoureux, K. (2018). Ensouling our schools: A universally designed framework for mental health, well-being, and reconciliation. Portage & Main Press.

- Linklater, R. (2014). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Fernwood Publishing.

- Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

- Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Venet, A. S. (2021). Equity-centered trauma-informed education. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Wong, A. (Ed.). (2020). Disability visibility: First-person stories from the twenty-first century. Vintage.

Articles

- Davidson, S. (2017). Trauma-informed practices for postsecondary education: A guide. Education Northwest, 5, 3-24.

- Boylan, M. (2021). Trauma-informed practices in education and social justice: towards a critical orientation. International Journal of School Social Work, 6(1).

- Field, M. (2016). Empowering Students in the Trauma-Informed Classroom through Expressive Arts Therapy. in education, 22(2), 55-71.

- Perry, D. L., & Daniels, M. L. (2016). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 8, 177-188.

Related essays on this site

Get more anecdotes and strategies like this one

Sign-up to my newsletter for professionals

By signing up for email alerts, you agree to receive updates and promotions to support you in your role in education or therapy. You can unsubscribe at any time.

0 Comments