Unschooling Explained: A Guide for Homeschooling Parents

Unlike traditional homeschooling, unschooling allows children to pursue their passions and interests without the constraints of a rigid curriculum. This makes it an appealing option for parents who want to foster independence, creativity, and a lifelong love of learning.

Is unschooling even possible for neurodivergent and disabled kids?

I am often asked if unschooling is even possible with/for neurodivergent and disabled kids, and the answer is a resounding “Yes!” This article is all about how and what unschooling could be for you.

In this article, we’ll cover:

- What unschooling is and why it’s a growing trend

- How unschooling differs from traditional homeschooling

- Practical tips for getting started if you’re new to unschooling

- Answers to common concerns and misconceptions about unschooling, including its application for neurodivergent and disabled learners

What is unschooling?

Unschooling is an educational philosophy where children learn through life experiences, self-directed play, and exploration instead of following a structured curriculum.

Aliah S. Richards, the author of Raising Free People, defines unschooling as “a child-trusting, anti-oppressive, liberatory, love-centered approach to parenting and caregiving. It is a way of life that is based on freedom, respect, and autonomy.”

Unlike traditional homeschooling, which sometimes mirrors the conventional school environment with lesson plans and exams, unschooling gives children the freedom to pursue their interests, whether delving into nature, exploring art, or mastering video games.

One thing to keep in mind is that unschooling is not not learning. Unschooling is removing the “schooling” part from learning.

“Schooling” refers to the:

- Rigid structure

- Fixed curriculum

- Standardization

- Tests and assessments

- Conformity to rules

- “Training” children to learn

- The power dynamic of “power over” children versus “power with”

- Time constraints

- Interruption to flow

For neurodivergent and disabled kids, removing “schooling” from education can be a game-changer.

Unschooling leaves the direction of learning up to the children themselves.

For the most part, this means children:

- Choose learning topics of interest to them. For neurodivergent/disabled kids, this is often referred to as “passion topics” or “special interests.”

- Work at a pace that is ideal for them.

- Spend as much time with the topic as they choose. It could be days; it could be months or lifelong!

- Choose the time of day to explore their interests.

- Choose what their exploration looks like. For some, it’s registering for a course; for others, it’s setting up a business; for others, it’s intense reading or watching videos; and for others still, it could be building a wagon with a neighbor who specializes in woodworking, etc.

- Weave learning into their daily rhythms and tasks, such as conversations during meals, problem-solving through conflicts with siblings, or the sights and sounds on the drive to the grocery store.

Integrating Academics into Daily Life Workshop

Discover how to integrate academics into daily life. For homeschoolers of neurodivergent and disabled learners.

Why is unschooling a feasible option?

Unschooling is a breath of fresh air in a world that often prioritizes standardized testing and rigid curriculums. It challenges the conventional education model, questioning the need for standardized instruction. Unschooling encourages real-world skills, creativity, and critical thinking, making it a flexible approach that allows children, especially neurodivergent and disabled learners, to flourish.

Unschooling is about fostering autonomy, agency, and interdependence—breaking away from oppressive structures that don’t cater to every child’s unique way of learning.

Unschooling challenges the conventional education model by questioning the need for standardized instruction. It has its roots in the educational reform movements of the 1960s, championed by educators like John Holt, who believed that children learn best when they are free to explore their interests without the pressure of grades or tests.

Homeschooling vs. unschooling: What’s the difference?

Parents often wonder if there’s a difference between homeschooling and unschooling. The short answer is: Yes! While both involve learning outside the conventional school setting, there are key distinctions:

|

Homeschooling |

Unschooling |

| Can range from highly structured to flexible, depending on the family’s preference | Emphasizes flexibility, with no set curriculum or schedule |

| Parents may use curricula, lesson plans, and educational resources to guide learning | Learning is driven by the child’s interests, with parents acting as facilitators rather than instructors |

| Often involves a mix of structured activities, planned lessons, and open exploration | Focuses on self-directed, interest-based learning without predetermined lessons |

| Can include formal assessments, testing, and grading, but not always | No formal tests or grades; assessment happens through observation and natural learning moments |

| Parents lead the planning, but there is room for child input, especially in flexible homeschooling styles | Children lead their own learning, deciding what, how, and when they want to learn |

Both homeschooling and unschooling offer opportunities for personalized, child-centered learning, but they differ in how much control the child has over their educational journey.

Unschooling doesn’t mean an absence of structure—it means the structure is fluid.

Benefits of unschooling

- Fosters independence and confidence

- Encourages deep learning

- Reduces stress and anxiety

- Promotes lifelong learning

- Empowers neurodivergent and disabled learners

School, after all, is a social construct. Learning, on the other hand, is natural.

How to approach unschooling: A practical guide

The irony of this list isn’t lost on me since unschooling isn’t about a step-by-step structure. But learning more about what unschooling is and is not will help you feel more confident about going with the flow in the long run.

1. Research

Before you make the switch, understand what unschooling really involves. Read books, join unschooling communities, and talk to other parents already doing it.

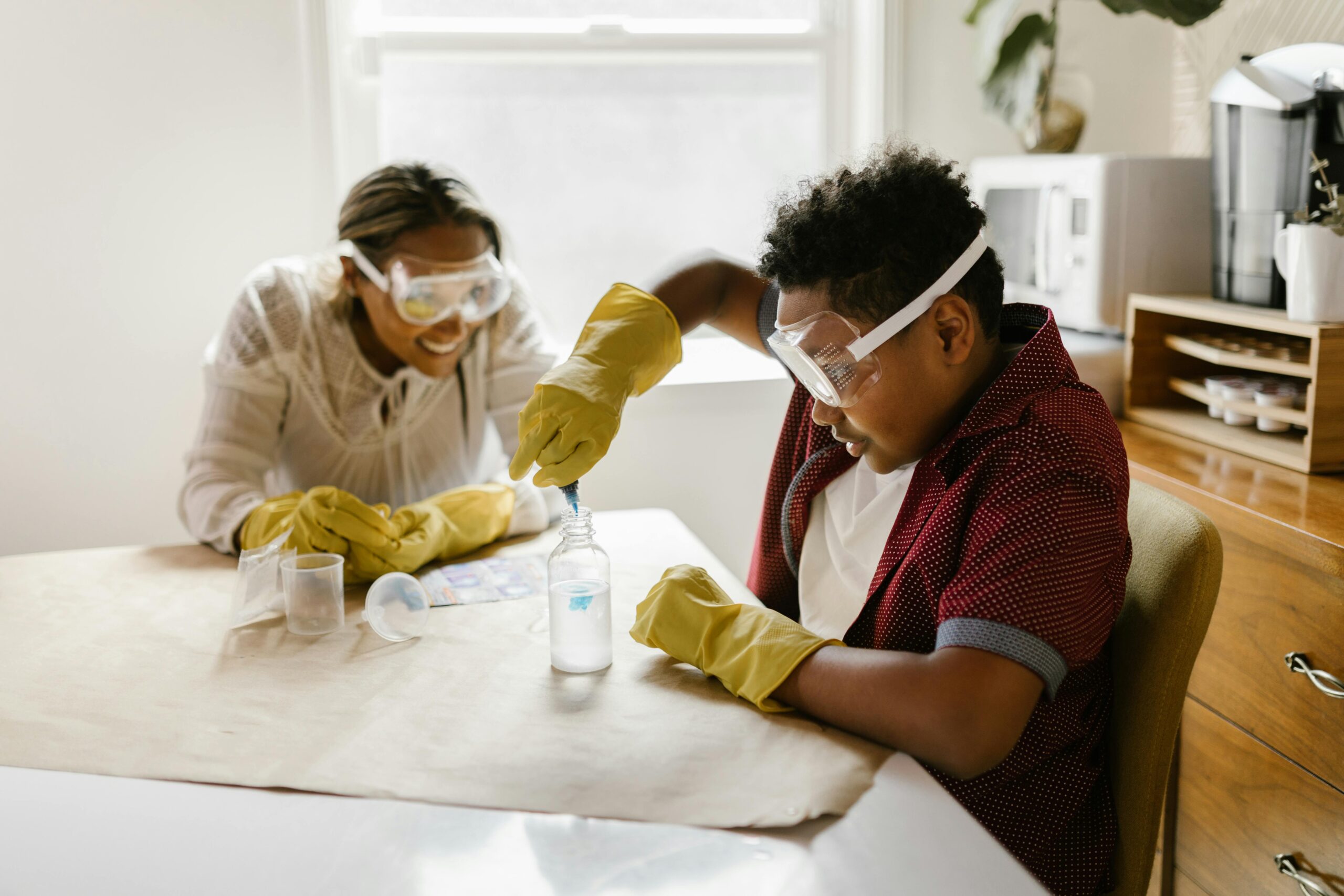

2. Observe

Observation is key. Watching and listening to your child can reveal how they naturally engage with the world, which can be the foundation of their learning journey.

If the essential principle of unschooling is letting kids take charge of their learning, how can our neurodivergent and disabled kids be given the power to “own it” and take charge of their education?

Make kids a part of the process by observing to enter their world.

When we observe our children and pay attention to their interests and needs, we can better understand how they learn and what they are most interested in. This allows us and our children to create a personalized learning experience tailored to their unique needs and interests rather than trying to fit them into a predetermined curriculum or agenda.

Observation can take many forms:

- Watching

- Listening

- Taking notes

- Videos and photographs

- Etc.

Observing allows us to:

- Identify the child’s natural strengths and interests.

- Get a better understanding of what works well for them and what may require more support.

- Gather and offer learning materials based on their interests.

- Track their progress over time (which is handy if we have to report to the Ministry of Education)

Things to keep in mind when observing:

- Observation is a continuous process.

- We must be open and flexible when observing as needs, interests, and skills may develop over long periods—but sometimes immediately.

On the other side of observation, the goal is to honor and support the child’s natural curiosity and desire to learn.

3. Create a flexible learning environment

While unschooling isn’t about strict schedules, that doesn’t mean no structure at all. Anchor your days around meals or activities that bring rhythm without rigid planning.

If learning is inherent, could your child learn

- during meals?

- on your daily walks?

- during personal care routines?

- at rest time?

- during free play?

- during shared reading?

- in the car?

- in a standing frame?

- in a walker?

- with family and friends?

- with caregivers?

- Etc.

4. Embrace the unknown

Unschooling can be unpredictable, and that’s okay. Be open to wherever your child’s curiosity takes them.

5. Envision your day

What would a perfect homeschool day look like for your family?

Engage in a visualization:

- What would it look like?

- What would it feel like?

- What would you do?

- What would you not do?

- What would you add?

- What would you take away?

- How would your child learn?

- How will your child progress?

Debunking myths about unschooling

Myth #1: Kids don’t actually learn

Reality: Children in unschooling environments learn deeply about subjects they are passionate about, often mastering skills not taught in conventional schools. Even simple activities like washing dishes can involve science, math, and problem-solving skills.

Myth #2: Unschooling is a free-for-all

Reality: Unschooling isn’t a free-for-all. It requires keen observation, intention, and trust. Planning in unschooling may look different, but it’s about guiding children to expand their knowledge based on their interests rather than enforcing a curriculum.

In many instances, it requires

- Keen observation

- Collaborative goal-setting

- Continuous communication

- Mutual respect

- Purposeful exposure to new things

- Deliberate learning opportunities

- A building upon and branching out of learning, and

- Enough freedom to hold it all

One of the defining features of unschooling is the ability to approach it at different levels and degrees of structure.

Myth #3: Unschooling isn’t ‘real’ education

Reality: Education isn’t confined to classrooms. Many successful individuals didn’t follow conventional educational paths. Unschooling celebrates different learning preferences in a variety of environments.

Myth #4: Unschooling doesn’t work for neurodivergent and disabled learners

Reality: As parents of neurodivergent and disabled learners, we may have somehow learned that our children cannot learn and would need “drill and kill” type strategies to acquire any skill. This is simply not true, as many self-advocates and researchers attest to. Everyone has interests; everyone can learn.

Daily rhythms create the repetition required for explicit instruction. Even if the topics change, the learning is anchored by those moments that remain constant, like personal care, meals, or bedtime. For neurodivergent/disabled kids, this could also be with transitions into mobility aids or on the way to therapy.

Unschooling invites a mindset shift from looking to the adults for solutions to entrusting our children with their own learning.

John Holt, author, and educator whose advocacy for unschooling was most prominent in the 70s and 80s, phrased it this way in his book How Children Learn, “We think in terms of getting a skill first, and then finding useful and interesting things to do with it. The sensible way, the best way, is to start with something worth doing, and then, moved by a strong desire to do it, get whatever skills are needed.”

Always presume competence—even in an unschooling setting.

Myth #5: We can’t unschool if we live in a strict province/state.

Parents might be hesitant about unschooling because they fear their strictly regulated province or state might not approve of this method of education.

I won’t go into the legalities of homeschooling or unschooling because the laws vary wherever you live. Instead, I encourage you to look into homeschooling regulations in your area.

With some preparation, it’s possible to show how your unschooled child is meeting educational standards that satisfy legal requirements.

For families contemplating unschooling who worrying about how to write reports for their unschooled children, I share two tips below on how to report to the Ministry of Education or any other authority that requires justification.

Keeping in mind that unschooling is a philosophy of education or an approach to education (and that most provinces/states leave the “how” up to the parents), the trick to explaining the “what” is mostly in the wording used on reports or in meetings. You don’t have to mention that you are an unschooling family at all.

Two tips for reporting when unschooling

1. Keep a record of the child’s learning experiences—whether reading books, playing games, doing art, exploring nature, cooking, gardening, outings, or pursuing their passions and interests, etc.

Many parents keep a portfolio of their child’s learning. I like documenting observations through photos of the activities and some anecdotal notes in a notebook. I also record progress, mainly by jotting down stories of things that have happened that show enthusiasm for something discovered or accomplished.

Keeping notes and photos will help remind you of the many things that happened throughout the year without having to present everything.

2. Provide examples connecting to educational standards. Once you’ve gathered learning experiences, find connections between your child’s interests/accomplishments and subjects like math, science, social studies, and language arts.

For example, if your child is interested in cooking, you can show how they learn about fractions and measurements in math, chemistry in science, and cultural traditions in social studies.

Did your child struggle with something for a while and then solve it on their own? That’s a problem-solving skill achieved! Did your child show an interest in a new topic? That’s self-motivation and self-direction. All of it counts!

You can reverse-engineer planning and reporting.

First, we do life; then, we fit the standards to what was tackled and accomplished. It’s amazing how many criteria you can tick off when you just live life!

Integrating Academics into Daily Life Workshop

Discover how to integrate academics into daily life. For homeschoolers of neurodivergent and disabled learners.

A day in the life of unschoolers – A case study

What does a day in the life of an unschooled disabled person look like? Here’s a sample from our home.

Morning

Wake. Depending on when my son wakes, he may spend some quiet time in bed with books or videos on his iPad.

Get up, personal care, and transfer to a chair.

Breakfast. While I unload the dishwasher and prepare breakfast, we either listen to podcasts or audiobooks and watch videos of books on tech. I let my son choose.

While we eat, we connect. I ask about what he’d like to do that day. I will model language through AAC, but he will also reply through AAC, ASL, or a low-tech AAC. I never force it.

I might say things like:

- “Remember when …”

- “I see you thinking about something. What are you thinking about?”

- “What do you want to do today?”

Sometimes, right after cleaning up and while he’s still in the chair, I might read him a story or play a board game.

Activity 1– Out of equipment. After breakfast, we engage in some activity on the floor or couch. When he was younger, we did Morning Circle. These days, I let him choose. It might be reading, free-play, or a review of another activity he engaged in that week.

Snack. Another transition back into the chair. Another touch-point for connection and casual conversation.

Activity 2 – In the walker. For the second part of the morning, my son is transferred into his walker, where we will engage in standing or movement-type activities. Again, I let him decide from a bunch of activities I have handy—all based on his recent interests. Sometimes, it’s a game or review activities with learning materials on a wall. Sometimes, he chooses to make some video calls at this time.

Free play while I prep lunch.

Afternoon

Personal care, transfer into chair, and lunchtime. This part is similar to the breakfast routine.

Activity 3 – At the table. Since we’re already seated at a table, we take on another activity—again, always providing choice and always letting my son decide.

Activity 4– Outdoors. Depending on the season and weather, this is the time we typically head outside. Sometimes, we build upon his interests outdoors, but often, it’s just for a stroll around the neighborhood to get some air.

Rest. A vital part of our day! Rest! Restoration! We do our own thing, silently, side-by-side. He often chooses his iPad while I read.

Personal care, transfer to chair, and dinnertime. Same as the breakfast and lunch routine.

Evening

Winding down the day. My son will do a video call with family or friends; I clean up and set up things for bedtime. We might fit in a story before bed, but not always. Sometimes, my son just wants the headspace to think.

Personal care, transfer to bed.

As parents of neurodivergent/disabled children, we somehow come to accept that things will be forever difficult.

We must put in extra effort to get our kids to “catch up.”

We have to do more because they have milestones to meet.

We are accountable to specialists’ reports and files. We have no choice.

This is simply not true. Not everything has to be complicated. And we do have a choice!

Unschooling offers a unique, flexible approach to education that empowers children to take charge of their learning.

While it may not be for every family, those who embrace it often find that it fosters creativity, independence, and a lifelong love of learning.

If other methods haven’t been a good fit for your child, or if you’re tired of rigid schedules, unschooling might be the perfect solution for your family.

Related articles

- Core Beliefs About Education

- Fostering Non-Judgement and Nourishing Compassion While Cultivating Freedom of Choice in Your Home

- Honing Passions: Using the Child’s “Fixation” as a Motivator for Learning

Resources

- Growing without Schooling – The work of John Holt

- Raising Free People Network – The work of Akilah S. Richards

- The Alliance for Self-Directed Education

References

Gray, P., & Riley, G. (2013). The challenges and benefits of unschooling, according to 232 families who have chosen that route. Journal of Unschooling & Alternative Learning, 7(14).

Michaud, D. (2019). Healing through unschooling. Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning, 13(26), 1-13.

Riley, G. (2023). Unschooling Students with Disabilities. Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning, 17(34).

Romero, N. (2018). Toward a critical unschooling pedagogy. Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning, 12(23), 56-71.

Integrating Academics into Daily Life Workshop

Discover how to integrate academics into daily life. For homeschoolers of neurodivergent and disabled learners.

0 Comments